That time of year approaches when any administrator, especially new to a building, devotes time and energy to intentionally designing opportunities to create team, as soon as staff walk in the door. Bringing together new and experienced educators into a cohesive team with a shared goal to make a place of belonging for every student can be a daunting task. Now try throwing 29 strangers, aged 20s to 60s, from 7 different countries into a foreign context, where they eat, sleep, and work together 24/7 and are tasked with nurturing their own team of teachers too…it has all the unpredictable potential of a memory-making nightmare conference camping trip.

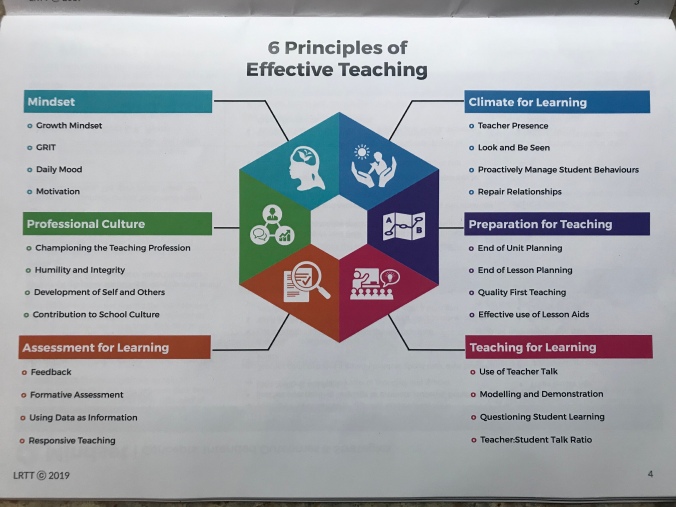

One might assume that a teacher identity would unify the group, until you consider your own past experiences with a variety of staff. In Uganda, the role of being a teacher did connect us to some degree. However, the vast diversity of values and beliefs around pedagogy, assorted backgrounds in education systems, range of years of experience, all contributed to a wide spectrum of ideas brought to the table and conversations. One critical way LRTT embraces this diversity is by pre-trip webinars and e-learnings but more importantly an LRTT guide that outlines the mission and equips the team to work towards the same goals. Once you land on the ground, LRTT leaders also respond to who’s in front of them.

As an administrator, I am reminded that we are all responsible for building a team. Sure, leaders can create optimal conditions, join together different teachers for different purposes, provide prompts that reveal connections, and offer food, of course. But sometimes, you need to let relationship building take its natural course. You find your peeps. You don’t have to love everyone, but you do have to be willing to work with everyone. An ultimate shared clear goal supercedes any personality or style differences. Even in disagreement or frustration, despite/in spite of the challenge, creativity can flourish. During our time in Uganda, LRTT leaders and its fellowship design proactively sought to combine different groupings of fellows, through PD preparation, school assignment, excursions, scavenger hunts, trivia nights, van seating…you name it. There was a myriad of ways to get to know each other.

If I try to connect the dots back to how me and my peeps established our squad, I remember the first day we arrived at the lodge…

[As an aside to frame this memory, I offer my biggest fear prior to heading to Uganda: not the food, not the job or location….it was sleeping. Sleeping is a precious commodity for me as I’m a particularly light sleeper. I don’t sleep in cars or on planes, and I can’t sleep with music or snoring! As a result, the very real possibility of sharing a room with 10-16 other people made my shoulders ache with tension. This could definitely be a dealbreaker.]

Once we were at the lodge, one of our fearless leaders declared that we were responsible for our sleeping arrangements, and they wouldn’t be assigned. Then came the magic words:”if you like quiet, you may enjoy the banda farthest from the action at the lodge.’ Say no more! I grabbed my belongings and hiked over to my home for the next month. And along came a trail of others:. My Uganda Banda Sistahs.

It’s funny how the choice of banda became a very first step in connecting us. Of course, the more conversations and common experiences we shared, the deeper our connections beyond sharing a banda.

I gained so much respect for these gals and came to rely on them for support, camaraderie, humour and fun. Here you are in a foreign and sometimes demanding environment where you share not only your story, but deodorant, towels, hiking boots, loo roll and well…outdoor washroom breaks. Three of us shared the same bedtime, love of reading and appreciation for the outdoors: Britt the birder, wildlife aficionado and bearer of a recent elephant tattoo, and Janet, the strongest and fittest of any of us by far. I adopted a 4th daughter, Katherine, who just finished a year of teaching in Zambia and will fit right in with my family if her mom lets her. She was a tough one to leave. No-nonsense Stephanie who teaches in Northern Ireland and also brought her experience of teaching in Ghana for LRTT last year. Emily the brave who at 24 years of age clearly has more chutzpah and future wild experiences than I! I’m desperate to visit my conference partner, tea-sipping Anna, the fearless but bruised mountain-biker, who returns to Katmandu for her fourth year of teaching, and riding. Or Sue, who actually had to move out of the banda partway through the month as she broke her arm chimp tracking (what a story!) and needed stable flat ground.

I will always cherish the friendships we made under unique circumstances. You become a little family who truly cares for each other, and it makes the trip’s demands that much easier to face. Together. Lucky for me, none of them snored! And if we can manage it, Java or Jordan may be on the horizon!

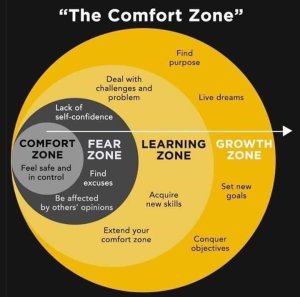

The anticipation of both moves saturates me at once with dread and excitement. I’ve been pondering a graphic for the past few days since

The anticipation of both moves saturates me at once with dread and excitement. I’ve been pondering a graphic for the past few days since